In order to best explain Mamoru Oshii’s Angel’s Egg––a stoic, ethereal vision quest of a film notorious among anime and cult enthusiasts for resisting explanation, and one which more readily invites comparisons to Cocteau, Tarkovsky, and Jodorowsky than other anime––it is necessary to explain Rumiko Takahashi. Takahashi, most famous in the West for her megahit manga Ranma ½ and Inuyasha (and their long-running anime adaptations), is the best-selling female comic creator in the world, a one-woman cultural institution who has continued putting out weekly serials at a steady pace for nearly half a century. Key to her success is her facility with character: behind her archetypal creations’ soft and rounded designs, gently idealized bodies, and large, expressive eyes lurk vividly outsized egos and libidinal desires that send them on cacophonous collision courses with one another, week after week, as Takahashi leverages her embrace of urban fantasy and screwball comedy to render wry observations on love, gender, family, and tradition. The results transcend boundaries: audiences (irrespective of age, gender, and nationality) continue finding something of their own passions and foibles in the petty rivalries, one-sided crushes, and hot-and-cold relationships that undergird Takahashi’s fantastical scenarios––located at a truly unique cross-section of sitcom and folklore––even as the author, rather notoriously, often struggles to move central storylines along.

“Character, story, worldview” are, in that order, what Mamoru Oshii describes as the creative priorities of anime production and mass entertainment generally. When he secured his first big job as a young director adapting Takahashi’s debut hit Urusei Yatsura for television, he was initially bound to these priorities, as in his 1983 debut feature, Urusei Yatsura: Only You––a light, colorful, visually dynamic character showcase for the anime’s expansive cast, cited by Takahashi as her favorite of the eventual six features based on the property. With the following year’s sequel, Beautiful Dreamer, Oshii was empowered to rebel. Taking the audience’s familiarity with the characters as a given, he crafted a singularly odd surrealist comedy which de-emphasized the series’ manic gags and romantic entanglements for a reflective, even subversive tone piece. Through a multi-perspective mystery structure, Beautiful Dreamer sees the Urusei Yatsura cast come to realize that they are trapped in a single character’s dream world, where the laws of gravity, perspective, and time no longer apply, and the same day––the day before the high school student festival––repeats itself unto infinity. As the cast continue their self-satisfied routines unabated, the rest of the world seems to vanish while the town––except for its key locations, the main protagonist’s home and school––begins to dilapidate and crumble. As characters ruminate on the nature of dreams and reality, punctuated by long shots of decaying or supernaturally warped urban landscapes, puddles of water become space-collapsing portals and supporting cast members start fading away. How long, the film asks, before the dreamer’s wish fulfillment is no longer enough to sustain the world? And who is really the one dreaming?

This was, as Oshii put it, a reversal of “character, story, worldview”: world and themes first, characters last. Audiences at the time (as well as Rumiko Takahashi) rebelled; Oshii soon found himself permanently departed from the Urusei Yatsura franchise. He was undeterred. His next major project, the direct-to-video feature Angel’s Egg, would take the “world, story, character” approach with a world and characters developed from scratch (a plan to develop it as a spinoff of the Lupin III franchise was scrapped early on). In so doing he would birth one of the most avant-garde works in the history of Japanese studio animation.

A collaboration with illustrator Yoshitaka Amano––a master of gothic fantasy and steampunk art best-known for his contributions to Final Fantasy and Vampire Hunter D––Angel’s Egg centers entirely on the construction of a somber, dreamlike, allegorical world through cryptic images and meditative silences. Oshii uses this world’s imagistic construction to create meaning for a stark spiritual parable, both dramatically unlike his subsequent films while containing the philosophical keys to nearly all of them.

The sparse, windswept world of Angel’s Egg is a place where no things have names and language is of limited use. Somewhere between a primordial fairytale and end-times prophecy, its visual trappings vaguely recall our world’s history, but unmoored from time and place as we know them. At the top of the world, embryonic, birdlike creatures slumber in great translucent eggs, the twitching of their eyes in slumber scored by church bells and a trembling, discordant Ligetian choir. The mechanical sun––a spherical flying fortress resembling a giant turquoise eye––ferries hundreds of human statues reminiscent of the Terracotta Army as it travels beneath a crimson sky; when it makes landfall on a checker-patterned walkway that seems to stretch infinitely into the horizon, its masses of slender steam chimneys (bunched together like ligaments) all shriek in unison. Its descent leaves only storm clouds and darkness. Rivers twist through forests of dying trees growing over ruins where giant armillary spheres lie half-buried; Stonehenge-like rock formations dot the otherwise empty plains. A baroque-looking coastal city lies seemingly abandoned, its building facades crumbling, its houses lifeless, stray objects littering the brick-paved streets gradually overtaken with flooding as the rain beats down ever harder. Statues of fishermen come to life to hunt the disembodied shadows of giant fish, further wrecking the city with their harpoons as the shadows swim across the streets and structures, indifferent. Red tanks roll through the streets, just recognizable as such beneath their carapace-like curves and tendon-like masses of cords that twitch and pulse as they move. Who is driving the tanks and where they are going is unknown––in the film’s view, inconsequential.

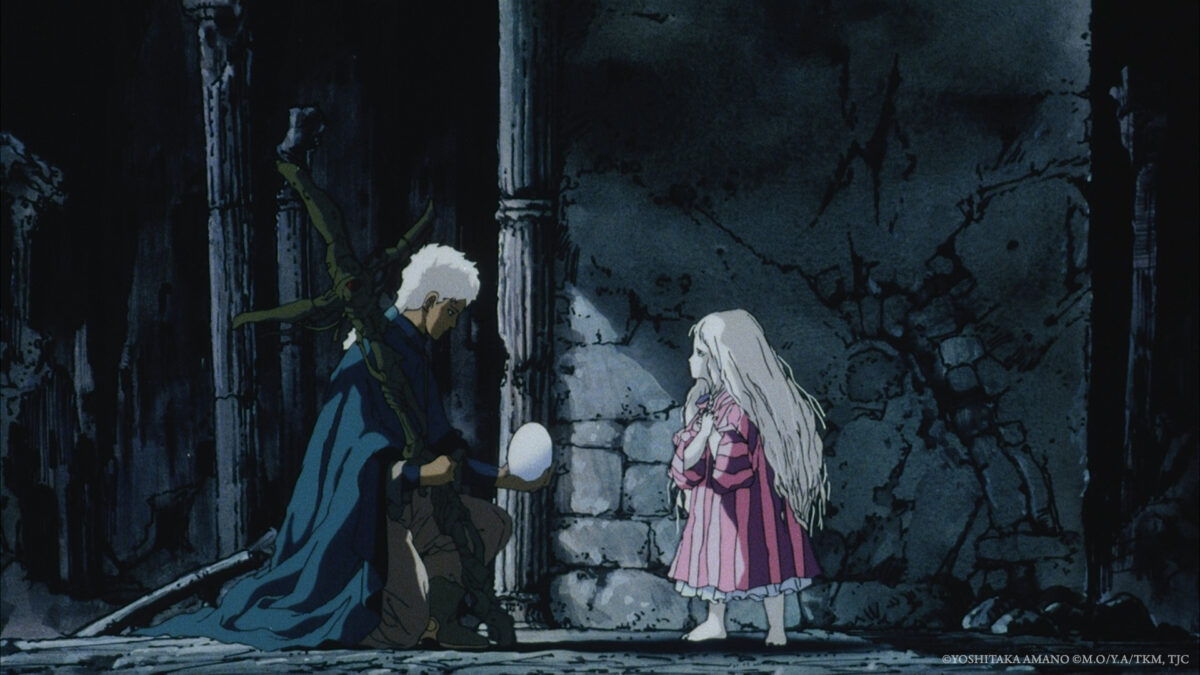

There are characters––two, to be exact. First, there is the man. His hair is long and white, contained in clasps and a ponytail. His skin is ruddy yet fine, lips pursed, half-moon eyes with penetrating, deep-black pupils sunk into his face. He does not flinch or blink as the waves of air from the great ship’s landfall toss back his hair and the dark-teal cloak draped over his plain clothing. While these sights are spectacular to us, he has, we may gather, seen it all before. Slung over his shoulder is a large, cross-shaped object made of metal parts. A sword? A gun?

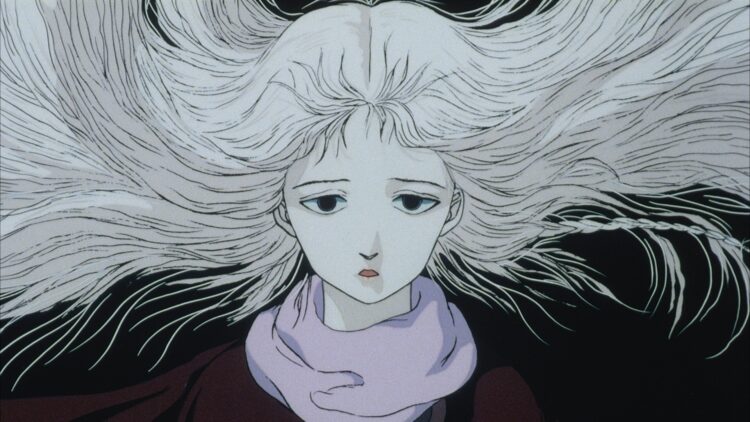

Then there is the girl. Her long, white hair, stringy and unkempt, flows freely down her shoulders and billows as she moves, sometimes becoming the main subject of the shot. Her skin is ghostly pale, eyes doll-like and sad. She carries a large egg; not so large as the monstrosities seen previously, but perhaps the size of an ostrich egg. She tucks it under her simple, magenta-striped dress as she journeys, making her appear pregnant despite her prepubescent body. When she cradles the egg, the wordless choir returns, now mournful and backed by delicate strings and piano. She seems to move with less than the weight of a person. When she turns to run, she spins on her heels like a dancer. She wanders through the land, determinedly, towards an unspoken destination; she stays close to rivers and streams, often gazing into the water, filling a spherical glass flask for travel. The camera mimics her staring into the water, dwelling often on the warping lines and shapes within sheets of nocturnal blue, on undulating eelgrass and strange artifacts half-buried in silt. At times, feathers flutter through the air and float on the water, though there are no birds or angels to shed them.

Much of Angel’s Egg is without dialogue, preferring Yoshihiro Kanno’s haunting score and the sounds of wind and rain while shots of dilapidated architecture, landscapes, and minute environmental details share significant screentime with the human protagonists. These contemplative landscape tours, with or without voiceover on top, would become an Oshii trademark even in his more conventional narrative films, establishing the centrality of “worldview” in his cinema: his characters cannot be divorced from the state of the worlds they inhabit. And his worlds, none more than Angel’s Egg, are lonely, cyclical, and slowly dying.

Much of Angel’s Egg is also without clear plotting behind its languid cascades of cryptic imagery, which is where it gains a reputation for losing first-time viewers. Scene to scene, the obscure rules of its world and surrealistic logic of its narrative, images, and cuts can feel so obtuse or so intimately tied to Oshii’s personal subconscious that the only substantive thing to grab onto can seem to be the wispy beauty of Amano’s artwork. There is, however, a point. Like many Oshii stories, Angel’s Egg centers around a dialectic: a female persona (associated with light and water, defiant of gravity) who pursues a dream of transcendence; and a male (associated with earth and metal, who moves with all the weight of the material world he inhabits) arguing for cynical realism yet haunted by the female’s image. As the man and girl meet and travel together, Angel’s Egg builds toward a single, pivotal dialogue that reveals the significance of the egg and telegraphs the film’s thesis via warped Biblical allusion: a poetic treatise on faith, transcendence, and the silence of God.

Critic Danielle Burgos notes that the purgatorial world of Angel’s Egg suggests nothing if not the Jewish hell of Sheol: not a place of fire and brimstone, but the world as it would be, dark and quiet, lacking God’s light and music. Judeo-Christian allusions are prominent in the eerie gnostic mythology: most obviously the story of the Great Flood and Noah’s Ark, with the New Testament’s virgin birth and treachery of Judas suggested in imagery and narrative alike. The unspoken synthesis of the film’s dialectic appears to be––if it can be put into words––that faith is both doomed and necessary, a lie whose belief might someday, if not today, make it true.

Equally fascinating is the creative DNA that Angel’s Egg would share with subsequent work from Oshii, both anime and live-action, just as it inherited several of its own motifs from Beautiful Dreamer. The girl’s voice actress, Mako Hyodo, would go on to become an Oshii mainstay, almost always playing one of the tragic dreamers, failed revolutionaries, and / or spectral female visages who haunt his body of work. Its flooded cityscapes would be reimagined with a near-future aesthetic in the Patlabor and Ghost in the Shell films; its glowing little girl and depopulated dreamworld would be visual touchstones in 2001’s Avalon; its mechanical designs’ uncanny fusions of the organic and industrial would prefigure similar motifs in Oshii’s hard science fiction, from the Kerberos armor’s subtle wolf motif to the winged helicopters and finned submersibles of Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence; its intimations of ideologically empty forever war would be expanded in The Sky Crawlers; its symbolism would even return in the lyrics to Innocence’s mesmerizing theme music (“They pray for the egg of the next world to be born”). The quest for transcendence (and consequences of its failure) in a false or decaying world––through politics, religion, or technology––would become Oshii’s thematic obsession, undergirding his films, screenplays, novels, and manga over and over again.

But as personally impactful as Angel’s Egg was for Oshii, its radical inversion of narrative priorities proved too alienating for audiences in its day. Whether they date or fight (or both), successful anime’s priority was and still is characters who inspire the identification or affection of the audience––or at least frenetic action if the writing falls through. Angel’s Egg, a film of almost pure mood and symbolism that seeks to slowly draw the viewer into the mysteries of its world, could not be much further from the extroverted, populist sensibilities of Rumiko Takahashi. As her star continued to rise, Angel Egg’s bombed––so hard that Oshii claims it put him out of work for years. (His next projects––a shorter video animation for a sci-fi anthology, Twilight Q, and his low-budget live-action debut The Red Spectacles, a confounding surrealist jaunt in its own right––debuted in 1987.)

But Angel’s Egg endured. Critics and industry professionals kept word of mouth alive, praising its uncompromising artistic vision and complete dissimilarity from any anime production before or since. It never received an official Western release (except spliced and redubbed into a low-budget live-action film from Roger Corman’s New World Pictures, sans Oshii’s approval), but Oshii and Amano’s pedigrees inspired curiosity while its reputation for narrative obscurity tempted cinephiles hunting for challenging fare. During the 21st century, amateur translations began to circulate online, dispelling (at least a bit) its air of mystery. 2010s online film culture, newly appreciative of anime, “slow cinema,” and “vibes,” discovered it anew. By the 2020s, it began receiving public screenings at film festivals and special venues in the United States and Europe. Now, newly restored in 4K (so sharp that attentive viewers may catch marks on the cel sheets), Angel’s Egg finally receives its first official U.S. release and theatrical run, taking its place alongside Ghost in the Shell among Oshii’s most internationally celebrated works. It remains one of a kind among anime to this day, and comes highly recommended both to arthouse fiends and genre fans seeking the sui generis.

Angel’s Egg has Dolby Early Access screenings on Wednesday, November 12 and will open in theaters nationwide on Friday, November 19. Learn more.

“Mamoru Oshii Restored: Origins and Inspirations,” including the new 4K restoration of The Red Spectacles, will begin at NYC’s Metrograph on Saturday, November 15. Learn more.

The post Mamoru Oshii’s Radical, Ethereal Angel’s Egg is an Anime Like No Other first appeared on The Film Stage.

from The Film Stage https://ift.tt/3jOUuLd

0 Comments