How do you pick up the pieces when your life falls apart? A Love Song director Max Walker-Silverman’s second feature Rebuilding is a wonderfully lived-in, empathetic folk tale of a movie following Josh O’Connor’s character after his house is burned down in a wildfire. While guiding his daughter (Lily LaTorre) and mending a relationship with his ex-wife (Meghann Fahy), O’Connor gives yet another staggeringly heartfelt performance centered on resilience and goodwill.

On the film’s opening day, I spoke with Walker-Silverman about the process of making his second feature, the mix of toughness and fragility of Josh O’Connor’s performance, the film’s stunning cinematography, how he knows what he’s gotten the right take, not wanting to do mean things to his characters, and more.

The Film Stage: Sometimes it takes quite a while for directors to make their second feature, so it was great to see Rebuilding come together quickly. What was the process of jumping right into it?

Max Walker-Silverman: I started writing it just after finishing A Love Song. There seems to be a process where a movie gives life purpose for a couple of years, and then it ends, leading to a moment of destitution and “what am I?” Then another silly idea pops into my head, and suddenly the fiction gives life purpose again. I finished post-production on A Love Song in the summer of 2021 in Mexico and went back home to Colorado. It was an especially smoky, tough, weird summer. Returning home and finding it odd, tough, and smelling of embers was a difficult transition after all the work on A Love Song. I had this image of a cowboy and a daughter in a fire, and then I was able to distract myself from reality for the next three years again.

Josh O’Connor has quite an autumn, with this being one of four films. Our reviewer said his performance in this film is so fragile, you feel like he could crumble if you look at him the wrong way. The emotional range he’s playing is so specific and heartfelt. I’m curious what kind of conversations you had with him and if the performance was calibrated from the start, or what it was like during shooting to ensure he was giving you exactly what you wanted.

I think this is why so many people are drawn to him and enjoy working with him. He has the most alluring thing in an actor, for me: someone who presents being both very tough and very fragile at the same time. You see that in many of his roles, even if the formalities of the performances and the worlds can be very different. That through line somehow connects the things he’s drawn to, and that’s what I was drawn to.

My role in working with him was largely about introducing him to the world and the cowboys. I put him to work on a ranch for a month or so. Beyond that, it was just about sharing my affection for the place and the people. That’s easy with him because he’s very easily charmed and finds delight in many things, which I really appreciate. So mostly that: sharing a tone of affection and then protecting a quiet workplace––protecting him and the other actors from the chaos of a film set––and letting him do his job.

How you and cinematographer Alfonso Herrera Salcedo capture him across these masterful vistas is incredible. I’m sure it’s more logistically complicated than a viewer might expect, trying to frame everything at the right timing. You did it in A Love Song and here, even on a larger scale. I’m curious how you worked with the DP?

You’re so vulnerable to nature on a movie like this when you’re mostly shooting outside. Alfonso is really great at reacting. We do a lot of planning on how we plan to shoot each scene, but ultimately it’s all guided by the actors and the camera placement, and the approach is based on what they do and the blocking they find. A lot of the real work is the scheduling and the collaboration between the cinematographer, the assistant director, and me. That’s an unheralded but critical part of the schedule because that determines what we’re shooting at dawn, what we’re shooting at sunset, and what we’re shooting during those eleven hours of bright overhead light.

A lot of what comes through as looking beautiful or not-so-beautiful is really the result of what time of day we’re doing this. It can be appropriate for certain scenes to look tougher and harsher and for others to be beautiful, but you only get one sunset every day, so you have to make the most of it. You just try to be prepared and schedule, and then react to whatever hail, rain, and snow you get thrown.

I love your editing style. The whole film feels like a folk song with the guitar interludes, and the score from Jake Xerxes Fussell and James Elkington is wonderful; Kurt Vile’s John Prine cover at the end is perfect. With that feeling you convey in the editing style, is it something you’re thinking about as early as the writing stage, or is it pieced together more in production or post-production?

Wow, that’s a very good question, and I don’t entirely know the answer to it. The rhythms of the dialogue and the performances inform a lot of that, and there’s definitely a through line from the script to the set that carries through to the editing. You probably couldn’t turn a lot of these scenes into crazy, back-and-forth witty banter, even if you wanted to. But then it is fun in the edit, working with Ramzi Bashour and Jane Rizzo, the editors, to find these moments, these interludes, like: when do things calm down or go quiet? It’s a mix. Sometimes the music comes in exactly as scripted and planned, and other times not so much.

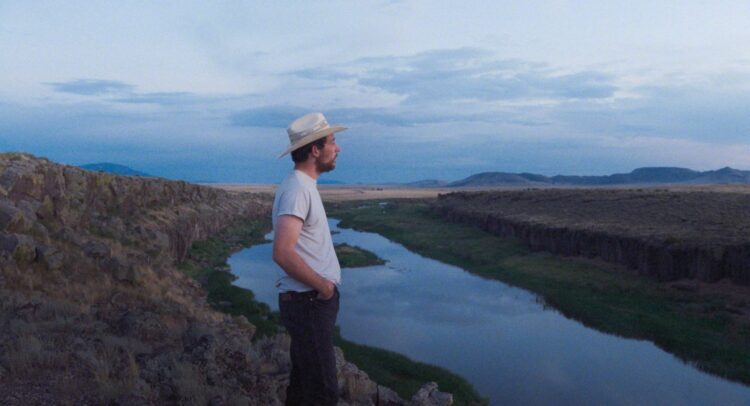

Max Walker-Silverman

While directing, how do you know how long to let a shot run? Are we seeing a lot of the take, or are you really letting things go and naturally unfold? I’m curious because you have some of supporting cast that are plucked from real life.

One might think that, with the supporting cast and non-actors, it’s more important to let things play out and leave things open. I kind of find it’s almost the opposite. With professional actors, like Josh O’Connor and Meghann Fahy in a scene, there will probably be long takes for every set-up, and you let them fill it out. For people who haven’t acted before, it’s such an unnatural thing that there’s going to be a lot more of, “All right, one shot, let’s get this one line. All right, we know we got this line.” It’s tough for someone who hasn’t done it before to work their way through a three-page scene and stay in the moment when there’s a big camera and Alfonso right in their face. So the set-ups get more granular, based on the performer, and also based on how much time you have. Very interesting. I’ve never been asked that.

Jefferson Mays, I’ve loved since Inherent Vice. He’s great in the scene where he’s presenting this impossible situation, where there’s no house and no farm to borrow against. I could see that being shot and scripted in a way that is impossibly bleak, but there’s this sense in Josh O’Connor’s character that even though he could just give up, he still has this hopeful nature, which runs throughout the film. How do you balance this mournful quality that’s not so bleak and still has a hopeful nature to it?

I just hate doing mean things to my characters. That’s not a good attribute as a writer at all, and it probably would be easier to make these movies if I was more inclined to make them do drugs and get in fights and stuff. I just can’t do it. So the script largely ends up being nice things, and then that doesn’t work for drama. So then you kind of need devastating circumstances, which I then put before the movie starts because it’s too sad. I don’t want to dramatize the worst day of someone’s life and make it look exciting and put it in a trailer or something, you know? So that happens before, and then the bad thing has already happened, and the circumstances are tough enough that, hopefully, you can tell a story of largely hope and kindness and decent people.

It’s tricky. There’s a formal challenge to that because you’re robbing yourself of most of what makes a movie propulsive and traumatic and good. But I like the challenge of it. I think it’s worth giving it a go, and yeah: there are no bad guys in the movie, and every character is kind of good, and I personally like that. It’s not going to work for everyone, but I think it’s worth doing. It’s worth giving it a shot.

One scene that really struck me was when Josh O’Connor’s character is walking with his daughter through the place his house burned down and discussing his hopes for where they could rebuild the house and where things could go. Is that based on anything in real life? It’s such a heartbreaking scene.

I mean, ultimately, the movie becomes about an act of life-reinvention or reimagination—about how to build things back differently. But it also felt important to acknowledge and even pay tribute to this amazing, crazy thing that humans also do, which is that there are also people who go and rebuild things just as they were. Maybe that’s remarkable, and maybe that’s insane. It’s kind of both, but regardless: it is fascinating and it is human, and I think we can all understand that instinct to bring things back to the way they were. Which one can never do entirely, but we try sometimes.

It’s interesting to think about how, sometimes when we’re thinking about the future, sometimes it’s really like we’re thinking about the past. And as we’re looking to move forward, sometimes we’re really looking to move back. That’s where the art comes in, I guess. There’s no answer to this. It doesn’t reduce into a sentence very easily, but it’s kind of amazing and strange and human, very human.

How do you think narrative films could help illuminate human struggles that headlines and other stories never could?

To start with: I truly believe in journalism. It’s amazing and critical and wonderful what journalism is and does. So I feel no instinct or pressure to try to replicate it. Because I admire it so much, I would not assume that I’m doing any of it. And so then you’re like, “All right, well, this story is not going to be journalistic. To me, it’s not about this. It’s not going to explain this subject necessarily.” Or like, “That’s not its job.” So I’m like, “What is its job? And what is the job of art? If journalism has a job to inform and illuminate, then what is the job of art?” And it’s the emotion of it. It’s the feeling, and then the imagining.

If the job of journalism is to explain what is, then maybe the job of art is to imagine what could be. I take that seriously, and I want the work to be grounded and honest, but also: there is some kind of dream to it and imagination. It might feel like delusion, but to me, it’s more like an optimism. That’s just how I think art should try to go about things.

Rebuilding is now in theaters and expands on Friday, November 14.

The post “I Don’t Want to Dramatize the Worst Day of Someone’s Life”: Max Walker-Silverman on Rebuilding and Josh O’Connor’s Fragility first appeared on The Film Stage.

from The Film Stage https://ift.tt/hDtKBn9

0 Comments