The characters in Kelly Reichardt’s films drift and wander. Her leads often work their way through the world, struggling against bad impulses and worse decisions, attempting to find community, solace, or calm. They’re working-class people on the margins, not remarkable unless in their capacity to keep on living a solitary existence. In The Mastermind, James Blaine “JB” Mooney––an excellent, moody Josh O’Connor––can’t seem to find stasis or success. And so he forms a plan: the heist of four Arthur Dove paintings at a local museum.

Set in the 1970s, Reichardt’s ninth feature is concerned with the aftermath of JB’s heist. A family man with two kids and a suburban life, JB is bored above all else. He’s toiling away in mediocrity, jobless and projectless. His grand ambitions do not match his current state in life, and to him, he deserves, desires, and needs more. O’Connor joins a line of Reichardt grifters and drifters, with the director dressing him in pastel sweaters while a jazz score beats in the background, more music than usual for the independent filmmaker.

The Mastermind finds Reichardt working in genre, blending comedy and slight tension, eventually––as always––landing in melancholy. Some familiar faces remain in the cast, with John Magaro wonderful as JB’s brother, while she fills the supporting cast with Bill Camp, Gaby Hoffmann, and Alana Haim, all wonderful in this small-scale heist drama. She remains a singular director, someone unwilling to cut her scenes short, focused on making work that pushes against audience expectations. The Mastermind is no different, and better off for it.

I chatted with Reichardt about constant surveillance in our everyday lives, The Mastermind‘s AMC secret screenings, and filmmaking as enjoyment rather than a career.

The Film Stage: Let’s see if we can chat about things that haven’t been covered.

Kelly Reichardt: Where did the idea of this film first come from? [Laughs] Which heist inspired it?

I’m actually reading a book right now called The Art Thief by Michael Finkel. It’s about a guy who is stealing loads of art because there’s a lack of security.

I think I know it, yes. Is it fiction or non-fiction?

It’s non-fiction and it came up when I was watching your film. There’s such a lack of security around these supposedly high-priced or important pieces of art. It made me wonder why we aren’t providing more security for these pieces we care about.

It was just a different time, right? Yeah. This kind of art heist, it’s barely a heist. They’re like snatch-and-grabs. I started collecting newspaper articles about them a long time ago, and I was just amazed at how much art gets snagged. It’s like retirees as security. The Gardner Museum is basically acid heads running the security. And they also had these great circular drives out front, which was handy. We shot in Cincinnati, and you can still find some good spots to shoot period. But there’s still things that had to be painted out in post, and most of that is security cameras. Forget museums. Every building, there’s cameras everywhere, everywhere, everywhere. When you start to really look what is on buildings, aside from cell phone towers and air conditioners and heaters, there’s cameras everywhere. And now you see, like on YouTube, how people have cameras all over inside their houses.

Do you think we’re devaluing the art at all by not having tighter security?

I don’t think it’s so much devaluing the art. I just think it’s a different time. How old are you?

I’m 29.

You’re young, so you can’t really imagine a world without fucking security shit everywhere. There’s a lot of upsides for not being filmed every second of your life wherever you are and, that not being the normalcy, I would say that what is more freakish to me isn’t the lack of security in the museums in the ’70s; it’s more how much you’re filmed everywhere you go all the time. And to me, that’s way freakier.

I’ve got to agree. I’ve heard you reference how the film starts with a heist and looks at the aftermath, similar to Night Moves. To me, it’s interesting how the movie starts with a man in community, with a family nearby, and then moves into isolation and loneliness. How do you make that large tonal shift when writing and directing a feature?

Everything is really a long process of trial and error. There aren’t really fast answers to these things. It’s just trying stuff and getting lost in the weeds and being lost for a while, and then figuring something out and being lost again, and then showing it to a friend and seeing if they can see something you’re not seeing, or what seems extra to a trusted eye. You wake up each day and reapproach it and then, at some point, it reveals itself, but not through any magic. Through work daily.

How do you know when it’s right, then?

It feels right suddenly. It feels like you’re ready, because you feel like you could show it to an actor, or you show it to someone outside your super-close circle of people that you give notes to.

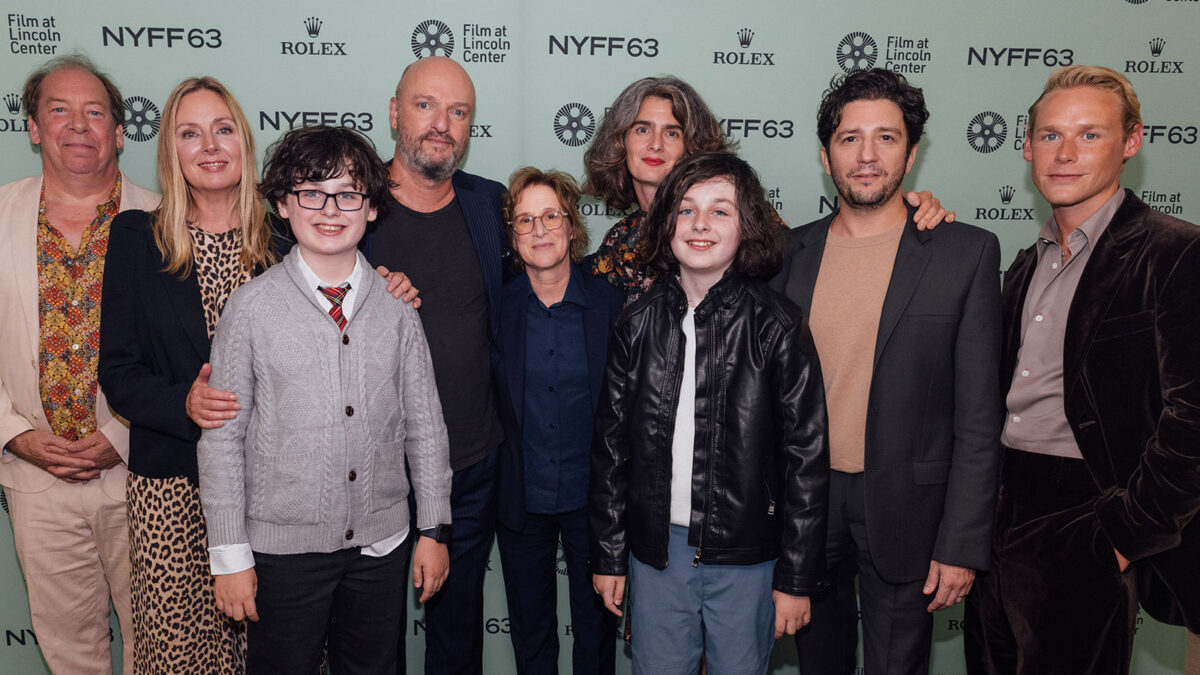

Kelly Reichardt at the cast of The Mastermind. Photo by Sean DiSerio/New York Film Festival

I’m curious about the ladder scene and the shot…

Jeez, jeez, jeez, jeez, jeez. I don’t really like giving my film away. I know it’s a hard job to talk about the film, but also don’t talk about the scenes in the film. You work so hard to have things reveal themselves in a certain rhythm and time, and then you go out for months and are supposed to talk about everything before anybody sees anything.

I can ask it in a different way, without revealing anything. There are scenes in this film that play out over a longer period than expected. And then there are certain moments the audience might expect to see which aren’t shown and get skipped over. How do you decide what gets shown and what gets cut?

Everything’s relative to what comes before it and what comes after it. Nothing stands on its own. Largely, filmmaking is considering time and space, aside from character. How you’re going to work it and how when you want to move people along, and when you want to allow people to move, especially if you’re working in a genre. Audiences are so narrative-wise. There was an article a million years ago––I think it might have been in the New Yorker. The gist of it was about comedies and the moment a laugh is supposed to be delivered. Even if you don’t achieve that moment, the audience is there and ready to laugh. That’s how fluid audiences are in genres of films. They know at 30 minutes what’s supposed to happen, just internally, and they know what comes next, and when that doesn’t get delivered or gets delivered in a different way, it can upset the viewer. Or it could maybe snap you up and wake you up into something more than a million cuts would or more than an escalating soundtrack or different ways of approaching tension.

It’s funny, because I guess there’s an AMC thing where people don’t know what they’re going to see.

I think I saw what you’re referring to. AMC played The Mastermind as a secret screening right?

I didn’t know about it until my friends told me, because I’m not on social media or anything. So my friend’s kid starts texting her mom, and her mom’s passing it on to me about how on TikTok and Reddit some people are just like, “I didn’t pay for the movie, I want my money back”. The anger that it caused in someone by not delivering what they feel entitled to have, like, “This isn’t what I ordered.” And somehow there’s a secret promise that’s an unspoken promise that’s been made––that you will deliver this and it was not delivered. I found it so interesting how some people go to see films to have an itch scratched that you want scratched, and some people go to films because of some other curiosity.

My point is––if I had one––that I’m not interested in making a film that’s already been made a million times. Most genre films aren’t like genres that came about by design from a multitude of people. White men have written all genres into design. You’re in these footprints that are there and there is a less aggressive, more observational approach to take to some of them. It’s not trying to pull a trick or anything; it’s just a different way of experiencing the world and how you experience time. People talk about slow cinema, but I feel the pace of things to be a constant assault on the senses. I think it’s completely commerce-driven and it’s about not seeing a lot.

I guess some people go to films because they want a totally emotional experience throughout, and people want not to be led along. One of the big complaints from the AMC crowd was that there was no message in the film, so what was the point? I believe that some of these voices are young voices, and I find it interesting how the difference in my generation of a young voice was about not buying into the status quo. I mean, who can blame anybody? It’s what you grow up with.

Behind the scenes of The Mastermind. Photo by Ryan Sweeney; courtesy of MUBI

Do you put weight into these audience reactions?

I don’t see them. I’m not on social media and I don’t really look stuff up, but this came to me and I found the anger towards it interesting. I teach for a living, for 30 years, so I’m not going to alter my filmmaking for it. I’m not like, “Let me please you.” But it’s interesting to me that young people could just be unsuspicious. I’m interested in how young people be with what, maybe, they’re not identifying as corporate power but it totally is.

Who’s teaching you to not question why you want the things you want? When I was young and I saw Douglas Sirk, I did not think it was fun. And when I took an Indian cinema class when I was young and I first saw Satyajit Ray films, I did not like them and I wondered why I had to see them. Then they grew on me and became, over time, just completely important. But I do remember being young and having reactions to things that I felt confused by, but I also felt I had an awareness of when someone was selling me something.

I do think people likely want, or at least accept, things that are more packaged nowadays.

I don’t see young people getting angry over franchise films. Why isn’t that? Why doesn’t that make you furious? It’s someone selling you something in a two-hour format that’s really about selling you something else and pretending. Why isn’t that infuriating to the 20-year-old?

Rather than the art heist film with Josh O’Connor.

Or just a scene that is just not cutting where you want it to cut. “It’s about nothing” is like the Seinfeld thing. I don’t know.

You’ve been making films for 30 years and teaching during that time, having this day-to-day job while also being a filmmaker. How do you think having this other job has affected your view of filmmaking and the process behind it? How has your relationship to filmmaking changed because of that?

Most filmmakers I know have eight projects going at once and they can juggle a lot, and I am such a one-trick pony; I just want to mull over one thing, and that’s it. We all have to pay our bills, and I have a teaching job. I’ve never presumed that filmmaking would make a living for me. That was not something that was happening in the ’90s for people like me, and so in the time I came up, it was not practical to think that way. I just didn’t ever think that way. Teaching has just become so a part of my filmmaking in my life. Particularly up at Bard, where I have been up for almost 20 years, and it’s just a space I like to be in. The two things really go together for me and it keeps the weight off.

When you’re younger, you just want to get a film made, and I’ve made some films now and I’ve gotten very close to the people I make films with. I like the process of writing to editing, but this one was an easier ride. First of all: it wasn’t COVID, which made a huge difference. And we had a little bit more money than I usually get, and that made a huge difference. The people I work with could bring some of their favorite people, and we just had a really great local crew and we weren’t shooting in the dead of winter or the peak of summer. And that makes a huge difference, because we shoot outside a lot.

There were hassles and it was hard, but filmmaking is really challenging. I didn’t feel like I couldn’t keep up with it, which was nice. I’ve been working with people like Chris Blauvelt [cinematographer] and Chris Carroll, the assistant director, and Tony Gasparro [production designer] for so long now that we’re not starting from scratch. We know how each other works. These are really deep collaborations. A great working collaboration is really one of the top things in life for me. Then Josh fell so easily into that, into our kind of world which was nice. It was a good experience. It doesn’t mean you’re not exhausted when it’s over, but you just know you’re lucky to be having the experience you’re having at the time.

I really enjoyed editing this film, and the whole thing allowed me to, quite frankly… we shot over the election, and when you’re shooting, you’re really in a bubble, and with editing, it gave me shelter. [Laughs] It’s like a hideaway. Not that that’s what one should be doing, but it was good while it lasted.

The Mastermind is now in theaters.

The post Kelly Reichardt on The Mastermind: “Question Why You Want the Things You Want” first appeared on The Film Stage.

from The Film Stage https://ift.tt/lnQag8Z

0 Comments